The original University of Chicago “uchicago news” article by Louise Lerner can be read here.

For decades, cancer researchers have longed for a way to target a set of proteins called transcription factors. While we’ve long known that tumors use these proteins to grow out of control, their unique configurations meant that for more than 30 years they had earned a reputation as “undruggable.” A group of University of Chicago scientists announced they have created an innovative way to build synthetic molecules that can target these previously “undruggable” transcription factors. The breakthrough result, which used data collected at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s)_Advanced Photon Source (APS) and was published in the journal Nature Biotechnology, holds promise for drugs and treatments as well as tools to better understand cancer biology.

“Doctors have had a hit list of transcription factors for decades, but we have lacked a way to target them,” said UChicago chemist Raymond Moellering, the senior author on the study. “This work sets the stage for letting us go directly for any transcription factor.”

As scientists have detangled the complicated workings of the cell, one thing that has become clear over the years is the importance of a class of proteins called transcription factors.

These proteins act like the pilots of the cell’s DNA, deciding which parts of the genome to turn on and off and when. This is an enormous power, which means they are a prime target for cancerous malfunctions. For example, the role of one well-known transcription factor called Myc is to turn cell growth on and off. If a tumor manages to hijack Myc, it’s like taping a brick to the gas pedal. The cells grow out of control.

“If you ask clinicians what they want in order to treat cancer, it’s a way to inhibit Myc,” said Moellering, an associate professor of chemistry whose area of expertise is developing new chemical tools and technologies to study proteins.

The problem is that Myc and its fellow transcription factors are big, made up of not just one protein, but several of them assembled together. The whole assemblies are so much larger than other proteins that scientists haven’t been able to make traditional drugs work on most transcription factors. “Using the traditional drugs on transcription factors is like trying to get a foothold on a 50-foot vertical cliff,” Moellering said.

So, scientists wanted to build a synthetic transcription factor. If this molecule could sit on top of Myc’s usual site on the genome, the researchers thought, it could prevent Myc from ordering the cell to grow out of control. But no one had managed to build a synthetic molecule that could do the job.

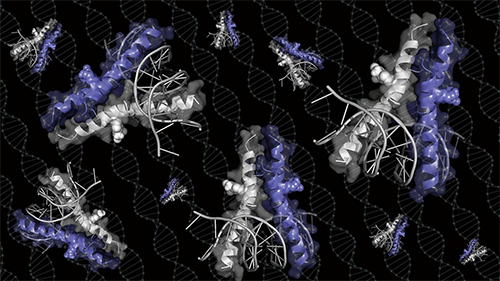

Moellering’s lab took a new approach. They built a synthetic molecule that borrowed part of Myc’s configuration—the claws that latch onto DNA. “Right away when we ran the gels, we could see that we had cracked the code for the right configuration,” said Moellering. They then determined the structure of the molecule using diffraction data collected at the Structural Biology Center’s 19-BM x-ray beamline of the APS, a DOE Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory, in order to study the molecule’s binding properties (Fig. 1).

The synthetic molecules bind very tightly to Myc’s landing point, preventing Myc from latching on. In petri dish tests, the molecules have successfully blocked the growth of cancer cells that are known to rely on Myc. These molecules are also compact enough to slip in and out of the cell, and stable enough to stick around for days before being broken down by the cell.

There is a long way before any molecule would be approved for use on humans, but they are seeing encouraging results in animal trials, the scientists said.

However, Myc is just one transcription factor. The team wanted to be able to customize the molecule to target many transcription factors. What they built is a customizable skeleton; based on their results, one could ‘reprogram’ that skeleton to target a different DNA sequence and thereby affect a different disease-causing transcription factor. This is partly because transcription factors aren’t just important in cancer; they are involved in everything from aging to diabetes to autoimmune disease. “In other diseases, maybe you want to turn on a set of genes instead of turning them off; or block one and turn up another,” said Moellering.

The synthetic molecules could also be used to help researchers better understand the mechanisms of cancer and other diseases—many of which remain mysterious. “There are many different directions where you could imagine using platforms like this,” said Moellering.

The scientists are working with the Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation at The University of Chicago to help commercialize the discovery.

See: Thomas E. Speltz1, Zeyu Qiao1, Colin S. Swenson1, Xianghang Shangguan1, John S. Coukos1, Christopher W. Lee1, Deborah M. Thomas1, Jesse Santana1, Sean W. Fanning1,2, Geoffrey L. Greene1, and Raymond E. Moellering1*, “Targeting MYC with modular synthetic transcriptional repressors derived from bHLH DNA-binding domains,” Nat. Biotechnol., published on line 27 October 2022. DOI: 10.1038/s41587-022-01504-x

Author affiliations: 1The University of Chicago, 2Loyola University Chicago

Correspondence: * [email protected]

The Structural Biology Center is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. The authors are grateful for financial support of this work from the following: the Virginia and D. K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research (to S.W.F. and G.L.G.); National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant T32 CA009594-34 (to R.E.M. and C.L.) and Medical Scientist Training Program grant T32GM007281 to J.S.C.; the V Foundation for Cancer Research (to R.E.M.); NIH grant DP2GM128199-01 (to R.E.M.); and American Cancer Society-North Central Research Scholar grant RSG-17-150-01-CDD (to R.E.M.). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.