The original Northwestern University press release by Megan Fellman can be read here.

Sparks literally fly when a sperm and an egg hit it off: The fertilized mammalian egg releases from its surface billions of zinc atoms in “zinc sparks,” one wave after another, according to research by scientists from Northwestern University who utilized the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS). Zinc fluctuations play a central role in regulating the biochemical processes that ensure a healthy egg-to-embryo transition, and this new, unprecedented quantitative information should be useful in improving in vitro fertilization methods.

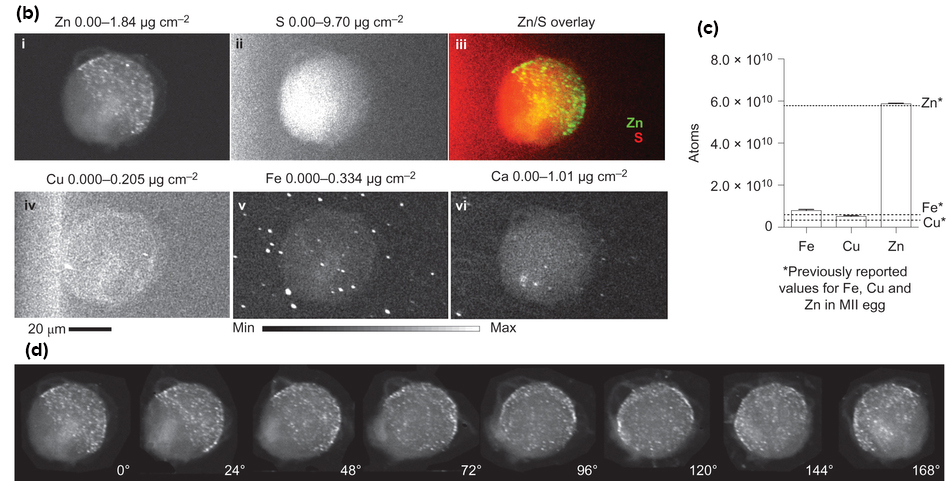

Using cutting-edge technology they developed, the researchers are the first to capture images of these molecular fireworks and pinpoint the origin of the zinc sparks: tiny zinc-rich packages just below the egg's surface, the first quantitative physical measurements of zinc localization in single cells in a mammal.

“The amount of zinc released by an egg could be a great marker for identifying a high-quality fertilized egg, something we can't do now,” said Teresa K. Woodruff of Northwestern, an expert in ovarian biology and one of two corresponding authors of the study that was published in the journal Nature Chemistry. “If we can identify the best eggs, fewer embryos would need to be transferred during fertility treatments. Our findings will help move us toward this goal.”

The research team, including synchrotron x-ray research experts from the APS at Argonne National Laboratory, developed a suite of four physical methods to determine how much zinc there is in an egg and where it is located at the time of fertilization and in the two hours just after. Sensitive imaging methods allowed the researchers to see and count individual zinc atoms in egg cells and visualize zinc spark waves in three dimensions.

After inventing a novel vital fluorescent sensor for live-cell zinc tracking, scientists discovered close to 8,000 compartments in the egg, each containing approximately one million zinc atoms. These packages release their zinc cargo simultaneously in a concerted process, akin to neurotransmitter release in the brain or insulin release in the pancreas.

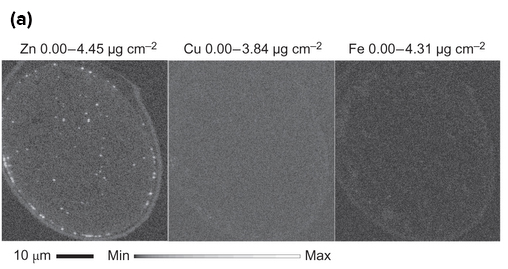

These findings were further confirmed with chemical methods that trap cellular zinc stores and enable zinc mapping on the nanometer scale in a custom-designed electron microscope developed for this project with funding from the W.M. Keck Foundation. Additional high-energy x-ray imaging experiments at the X-ray Science Division 2-ID-E and Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team (LS-CAT) 21-ID-D x-ray beamlines at the APS, an Office of Science user facility, enabled the scientists to precisely map the location of zinc atoms in two and three dimensions.

“On cue, at the time of fertilization, we see the egg release thousands of packages, each dumping a million zinc atoms, and then it's quiet,” said Thomas V. O'Halloran of Northwestern, the other corresponding author. “Then there is another burst of zinc release. Each egg has four or five of these periodic sparks. It is beautiful to see, orchestrated much like a symphony. We knew zinc was released by the egg in huge amounts, but we had no idea how the egg did this.”

The study establishes how eggs compartmentalize and distribute zinc to control the developmental processes that allow the egg to become a healthy embryo. Zinc is part of a master switch that controls the decision to grow and change into a completely new genetic organism.

The studies are the culmination of six years of work and build on prior discoveries made by the Woodruff and O'Halloran labs using data from work performed at Northwestern and the APS. In previous studies in mouse eggs, this research team discovered the egg's tremendous zinc requirement for reaching maturity. In addition, the researchers determined that an egg loses 10 billion of its 60 billion zinc atoms upon fertilization in a series of four or five waves called zinc sparks. Release of zinc sparks from the egg is essential for embryo formation in the two hours following fertilization.

“The egg first has to stockpile zinc and then must release some of the zinc to successfully navigate maturation, fertilization and the start of embryogenesis,” O'Halloran said. “But exactly how much zinc is involved in this remarkable process and where is it in the cell? We needed data to better understand the molecular mechanisms at work as an egg becomes a new organism.”

One major hurdle the O'Halloran and Woodruff team faced was the lack of sensitive methods for measuring zinc in single cells. To address this problem, they formed a collaborative team with other researchers in Northwestern's Chemistry of Life Processes Institute to develop the tools they needed.

Key members of the team were Vinayak P. Dravid of Northwestern, and Stefan Vogt, at the APS. Dravid and Vogt are co-authors of the paper.

“We had to develop a slew of methods to be convinced we were seeing the right thing,” O'Halloran said. “Science is about testing and retesting ideas. All of our complementary results point to the same conclusion: the zinc originates in packages called vesicles near the cell's surface.”

The researchers currently are working to see if they can correlate zinc sparks with egg quality, information that would be key to improving fertility treatments.

Not only are these new imaging techniques important for describing the zinc spark, they can be applied to other cells that likely use zinc in a similar way, but whose workings remain elusive due to the lack of sensitive and specific tools. This study lays the groundwork for understanding how zinc fluxes can regulate events in multiple biological systems beyond the egg, including neurotransmission from zinc-enriched neurons in the brain and insulin-release in the pancreas.

See: Emily L. Que1, Reiner Bleher1, Francesca E. Duncan1, Betty Y. Kong1, Sophie C. Gleber2, Stefan Vogt2, Si Chen2, Seth A. Garwin1, Amanda R. Bayer1, Vinayak P. Dravid2, Teresa K. Woodruff1,* and Thomas V. O’Halloran1**, “Quantitative mapping of zinc fluxes in the mammalian egg reveals the origin of fertilization-induced zinc sparks,” Nat. Chem., advanced online publication, (December 15, 2014). DOI: 10.1038/NCHEM.2133

Author affiliations: 1Northwestern University, 2Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: ** [email protected], * [email protected]

Three QuickTime movies are available at the following:

http://www.nature.com/nchem/journal/vaop/ncurrent/extref/nchem.2133-s2.mov XFM tomography Zn maps and live cell fluorescence Zn staining have identical distributions in the MII egg. XFM zinc maps of a sulfide-treated MII egg at different angles (left, angle indicated in lower right corner) demonstrate an identical hemispherical, cortical distribution of zinc to that observed using live cell fluorescence imaging of ZincBY-1 (50 nM, green) and Hoecsht (1 μg/mL, blue) stained MII eggs.

http://www.nature.com/nchem/journal/vaop/ncurrent/extref/nchem.2133-s3.mov The zinc spark imaged in three dimensions. Three-dimensional reconstruction of changes in intracellular (50 nM ZincBY-1, green) and extracellular (50 μM FluoZin-3, red) zinc during egg activation with 10 mM SrCl2. Hot spots of zinc exocytosis are visible throughout a spark event.

http://www.nature.com/nchem/journal/vaop/ncurrent/extref/nchem.2133-s4.mov Cortical zinc vesicles are lost during the zinc spark. Confocal imaging of intracellular (50 nM ZincBY-1, green) and extracellular (50 μM FluoZin-3, red) zinc during egg activation with 10 mM SrCl2 reveals a loss of cortical zinc-rich vesicles at the time of the zinc spark.

This work was supported by The National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant U54HD076188) and the W.M. Keck Foundation supported the research. A.R.B. is supported by CLP Training Grant 5T32GM15538-02.The Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team is supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (Grant 085P1000817). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.