The original Los Alamos National Laboratory press release by Kevin Roark can be read here.

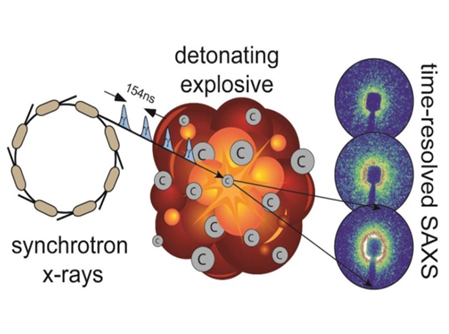

For the first time in the U.S., time-resolved small-angle x-ray scattering (TR-SAXS) experiments, carried out at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory, were used to observe ultra-fast carbon clustering and graphite and nanodiamond production in the insensitive explosive Plastic Bonded Explosive (PBX) 9502, potentially leading to better computer models of explosive performance.

“Carbon clusters are produced during the chemical process of detonation in high explosives,” said Dana Dattelbaum of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Explosive Science and Shock Physics Division. “The carbon particle size, shape, composition and their evolution in time helps us understand how explosives deliver energy over a given time frame.”

The research was published in the online version of the Journal of Physical Chemistry (C).

Using the TR-SAXS technique in the 35-ID-B research station of the newly-commissioned Dynamic Compression Sector at the APS, researchers from the Los Alamos, Lawrence Livermore, and Argonne national laboratories and Washington State University detonated small samples of TATB-based (triamino trinitrobenzene) PBX 9502 while high-brilliance x-rays were scattered by the solid carbon products formed in the detonation. (The APS is an Office of Science user facility.)

PBX 9502 is an insensitive high explosive that is widely used in the U.S. nuclear deterrent. High explosives are used to drive the nuclear “primary” to a critical mass, initiating a nuclear detonation. Insensitive high explosives are very difficult to detonate accidentally, and are considered extremely safe. However, the exact chemical process of energy transfer is still largely unknown.

The researchers found that the creation of carbon clusters happens much faster than previously thought, and the composition of the carbon is very different than had been assumed.

“An unexpected and significant finding of this research was the ratio of graphite to diamond inferred by the x-ray contrast from the scattering measurements,” said Dattelbaum. “In detonating TATB-based PBX 9502, we found that approximately 80 percent graphite and 20 percent diamond was formed when we were expecting to see a much higher percentage of diamond-like carbon.”

The products of detonation, the particle size dynamics, and type of carbon produced can correlate directly to the type of explosive, and improving computer models of explosive performance, leading to better predictive capability in assuring the safety, security, and effectiveness of the U.S. nuclear deterrent.

Analysis of the x-ray scattering data from the TR-SAXS studies revealed rapid initial growth of carbon clusters within 200 nanoseconds behind the shock wave front in the three-gram explosive sample. Analysis of recovered products revealed that particle size did not exceed a diameter of 8.4 nanometers, and that particle size confirmed that the particle growth did not continue after 200 nanoseconds for this charge size.

“What we’re really trying to do is understand how this process evolves over time,” Said Dattelbaum, “so we can better predict the velocity and energy delivered by a given explosive.”

See: Erik B. Watkins1, Kirill A. Velizhanin1, Dana M. Dattelbaum1*, Richard L. Gustavsen1, Tariq D. Aslam1, David W. Podlesak1, Rachel C. Huber1, Millicent A. Firestone1, Bryan S. Ringstrand1, Trevor M. Willey2, Michael Bagge-Hansen2, Ralph Hodgin2, Lisa Lauderbach2, Tony van Buuren2, Nicholas Sinclair3, Paulo A. Rigg3, Soenke Seifert4, and Thomas Gog4, “Evolution of Carbon Clusters in the Detonation Products of the Triaminotrinitrobenzene (TATB)-Based Explosive PBX 9502,” J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 23129 (2017). DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b05637

Author affiliations: 1Los Alamos National Laboratory, 2Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 3Washington State University, 4Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *[email protected]

The authors acknowledge support from the U.S. Department of Energy-National Nuclear Security Administration (DOE-NNSA) and the Dynamic Material Properties program. The research is funded by the National Nuclear Security Administration as part of Science Campaign 2 in support of the Stockpile Stewardship Program. User facilities include the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies and the Dynamic Compression Sector at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne. This publication is based upon work performed at the Dynamic Compression Sector supported by the U.S. DOE-NNSA under Award Number DENA0002442 and operated by Washington State University. This work was performed, in part, at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, which is funded by DOE-Basic Energy Sciences. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02- 06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.