The Argonne National Laboratory press release by Carla Reiter can be read here.

Extraordinary things happen to ordinary materials when they are subjected to very high pressure and temperature. Sodium, a conductive metal in normal conditions, becomes a transparent insulator; gaseous hydrogen becomes a solid.

But generating the terapascal pressures — that's ten million times the atmospheric pressure at the earth's surface — needed to explore the most extreme conditions in the laboratory has been possible only with the use of shock waves, which generate the pressure for a very short time and then destroy samples. Now an international team working at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Advanced Photon Source (APS), a DOE Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory, has devised a method for achieving static pressures vastly higher than any previously reached.

"Achieving ultra-high pressures opens new horizons for a deeper understanding of matter," said Leonid Dubrovinsky, a scientist at the University of Bayreuth, Germany, who was one of the developers of the new method. "It is of great importance for the fundamental sciences, for modeling the interior of giant planets and for the development of novel materials with unusual properties for technological applications."

Using an innovative new device that employs transparent nano-crystalline diamonds developed for this application, Natalia Dubrovinskaia, who led the study, Dubrovinsky and collaborators achieved pressures almost 50 percent higher than the highest static pressure reached previously with standard single-stage diamond anvil cells.

"It is a huge step," said Vitali Prakapenka, a scientist at the Center for Advanced Radiation Sources at the University of Chicago, who worked on the experiments.

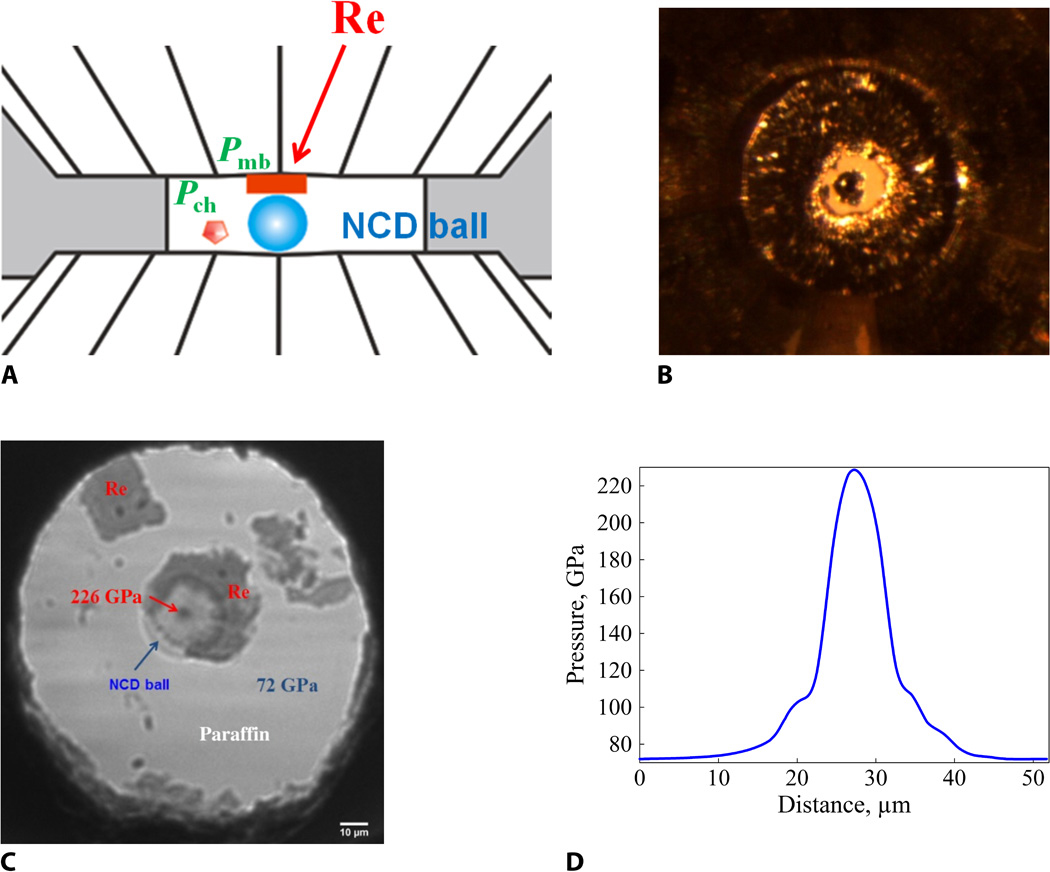

Dubrovinsky and colleagues designed a version of a double-stage diamond anvil cell typically used to generate high pressures. The traditional apparatus works like a vice that squeezes the sample between two single-crystal diamonds. In the new device, a miniscule ball of nano-crystalline diamonds sits atop each single-crystal diamond. As the diamonds are squeezed together, the load is transferred from the larger diamond to the nano-ball. The nano-diamond balls compress and actually get harder, allowing them to both generate and withstand extreme pressures.

The researchers further extended the capabilities of the apparatus by introducing a gasket assembly that acts as a secondary pressure chamber inside the cell, allowing them to work with gases and liquids as well as solids.

The transparency of the new nano-diamond balls opens the possibility for achieving high pressure and high temperature simultaneously. "We can shine the high power laser through the diamond anvil and through the nano-diamond as well, and heat the sample when it's already pressurized," said Prakapenka. "And we can then probe the sample properties in situ with synchrotron X-ray techniques."

This ability to probe matter at ultra-high static pressures has important implications for understanding the physics and chemistry of materials. The most direct immediate application is to the study of the materials under tremendous pressure on the interiors of the giant planets. But Prakapenka suggests other possibilities.

"We can synthesize absolutely new materials with unique properties that we would never have predicted," he said. "And we believe that there still exist some materials that we can synthesize only at high pressure, like superconductors, and then quench down, bring to ambient conditions and use. In this case it's a very small amount — it's only microns — but for the future application in nano-robotic technology, who knows."

The group worked at the GeoSoilEnviro Consortium for Advanced Radiation Sources (GSECARS) 13-ID-D beamline, which is operated by the University of Chicago at the APS. The high intensity and energy of the APS X-ray beams were crucial for the experiments. "The beam should be intense enough to go through the diamond anvil and through the one- or two-micron sample and give you enough statistics to see diffraction from the sample," said Prakapenka. "You need very high-intensity, high-energy X-rays to do that. It's only possible at third-generation synchrotrons like APS."

Also critical were the GSECARS monochromator, optics, and imaging systems, which bring the beam to the sample position, focus it down to a spot less than three microns and let the scientists see and analyze the sample in situ.

See: Natalia Dubrovinskaia1*, Leonid Dubrovinsky1, Natalia A. Solopova1, Artem Abakumov2‡, Stuart Turner2, Michael Hanfland3, Elena Bykova1, Maxim Bykov1, Clemens Prescher4, Vitali B. Prakapenka4, Sylvain Petitgirard1, Irina Chuvashova1, Biliana Gasharova5, Yves-Laurent Mathis5, Petr Ershov6, Irina Snigireva3, and Anatoly Snigirev3,6, "Terapascal static pressure generation with ultrahigh yield strength nanodiamond," Sci. Advances 2 (7), e1600341-1 (2016). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1600341

Author affiliations:1University of Bayreuth, 2University of Antwerp, 3European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, 4The University of Chicago, 5Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, 6Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University ‡Present address: Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology

Correspondence: *[email protected]

N.D. thanks the German Research Foundation [Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)] and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; Germany) for financial support through the DFG Heisenberg Programme (projects no. DU 954-6/1 and DU 954-6/2) and project no. DU 954-8/1 and the BMBF grant no. 5K13WC3 (Verbundprojekt O5K2013, Teilprojekt 2, PT-DESY). L.D. thanks the DFG and the BMBF (Germany) for financial support. GSECARS is supported by the National Science Foundation Earth Sciences (EAR-1128799) and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) GeoSciences (DE-FG02- 94ER14466). A.S. thanks the Ministry of Science and Education of Russian Federation through grant no. 14.Y26.31.0002 for financial support. This research used resources of the APS, a DOE Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract no. DE-AC02- 06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.