The University of California, Irvine, press release can be read here.

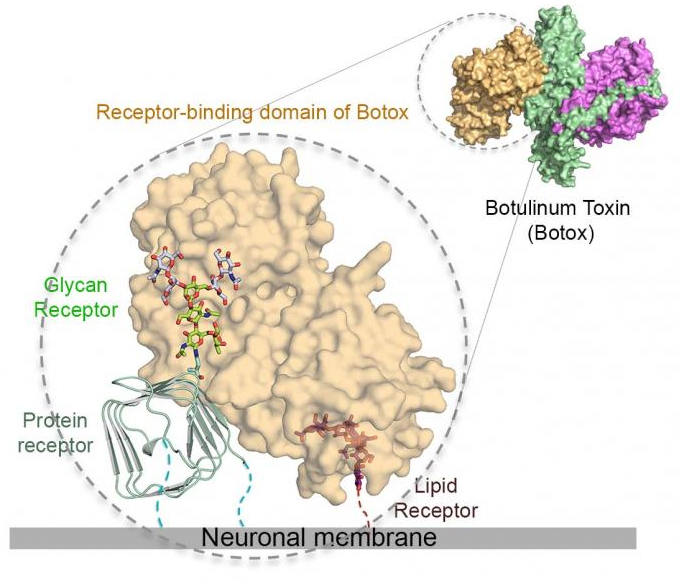

The Botox toxin has a sweet tooth, and it's this craving for sugars — glycans, to be exact — that underlies its extreme ability target neuron cells in the body while giving researchers an approach to neutralize it. A study by researchers who employed the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) revealed an important general mechanism by which the pathogen is attracted to, adapts to, and takes advantage of glycan modifications in surface receptors to invade motor neurons. Glycans are chains of sugars synthesized by cells for their development, growth, functioning or survival.

“Our findings reveal a new paradigm of the everlasting host-pathogen arms race, where a pathogen develops a smart strategy to achieve highly specific binding to a host receptor while also tolerating genetic changes on the receptor,” said study co-leader Rongsheng Jin, professor of physiology and biophysics at the University of California, Irvine. “And to some extent, this mechanism by which the toxin attacks human is similar to the one that is utilized by some important broad-neutralizing human antibodies to fight viruses, such as dengue viruses and HIV.”

Botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT/A), commonly known as the Botox toxin, is widely used in a weakened form for treating various medical conditions as well as for cosmetics. The clinical product Botox contains extremely low doses of the toxin and is safe to use. But at higher doses, it can be lethal, and it's also classified as a potential bioterrorism agent.

Its potency and therapeutic effects rely on its extraordinary ability to target motor neurons and subsequently block release neurotransmitters that control the movement of muscle fiber, which can result in paralysis. This specific targeting is achieved by highly selective interactions between the toxin and its receptors — host proteins that bind to the toxin in a lock and key manner.

The intricate detail of how the Botox toxin recognizes its receptors also reveals novel ways to neutralizing these deadly toxins.

Key to these new insights was determination of the structure of the BoNT/A1 receptor-binding domain (HCA), obtained via x-ray diffraction in collaboration with beamline scientists at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (NE-CAT) beamline 24-ID-C at the APS (the APS is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne) by researchers from the University of California, Irvine; Harvard Medical School, the Hannover Medical School (Germany), the Robert Koch-Institut (Germany), and the Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope.

“With this new structural information,” said study co-leader Andreas Rummel of the Hannover Medical School (Germany), “we were able to pinpoint key amino acids in the toxin that are required for binding to sugars, and we found that even mutating a single amino acid is sufficient to abolish the toxicity by more than a million fold.”

Remarkably, the newly mapped glycan-binding site turns out to be also the site recognized by a potent human neutralizing antibody called CR2/CR1, which is currently in clinical trial for the treatment and prevention of BoNT/A poisoning. “This antibody fights the toxin exactly by preventing it from binding to sugars on the receptor. Our study thus provides a new strategy for anti-toxin inhibitor design,” said study co-leader Min Dong of Boston Children's Hospital-Harvard Medical School.

See: Guorui Yao1, Sicai Zhang2, Stefan Mahrhold3, Kwok-ho Lam1, Daniel Stern4, Karine Bagramyan5, Kay Perry6, Markus Kalkum5, Andreas Rummel3***, Min Dong2**, and Rongsheng Jin1*, “N-linked glycosylation of SV2 is required for binding and uptake of botulinum neurotoxin A,” Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., published online 13 June 2016. DOI: 10.1038/nsmb.3245

Author affiliations: 1University of California, Irvine, 2Harvard Medical School, 3Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, 4Robert Koch-Institut, 5Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope, 6Cornell University

Correspondence: *[email protected], **[email protected], ***[email protected]

This work was partly supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants R01AI091823 and R21AI123920 to R.J. and R01AI096169 to M.K.; by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant R01NS080833 to M.D.; and by Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung grants FK031A212A to A.R. and FK031A212B to B.G. Dorner (RKI). NE-CAT is funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P41 GM103403). The Pilatus 6M detector at the 24-ID-C beamline is funded by a NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10 RR029205).

This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.